Sajida Tuxun is a Lecturer of Cultural Anthropology at Duke Kunshan University and a member of the CSCC Meanings, Identities, and Communities Cluster. Her research focuses on the intersection of food, ethics, and consumerism in urban China, with broader interests in globalization, gender, ethnicity, and mobility. Through the lens of food anthropology, her work examines how dietary practices are shaped by social values, cultural traditions, and evolving health discourses. Sajida’s CSCC-supported research project, “Consuming Food, Consuming Ethics,” explores the cultural meanings and ethical dimensions of healthy eating in urban China, with fieldwork conducted in restaurants, confinement centers, and organic farming communities across several regions. By combining participant observation, interviews, and online ethnography, the research offers insight into how food consumption is shaped by broader social, environmental, and policy dynamics. We spoke with Professor Tuxun to learn more about her research, recent findings, and the evolving questions that continue to shape her work.

Thank you so much for joining us today, Professor Tuxun. To start, your most recent CSCC-supported project focuses on food ethics and the meaning of a “healthy diet” in urban China. Could you share with us what inspired you to pursue this topic, and tell us a bit more about the project?

In my exploration of migration, food, and gender, I have discerned a significant oversight: the nuanced role of food often escapes scrutiny in the broader discussions of these themes, despite its daily prominence in our lives. In recent years, a noticeable shift toward healthier living has emerged globally, with plant-based diets, vegetarianism, and veganism, marking a significant trend in China’s urban centers. Upon my arrival at DKU, this subject became my major focus. This inquiry into food becomes even more pronounced when considering the intersection of food with critical issues such as ethics and the environment. The aim of my CSCC project is twofold: to unravel the intricate relationship between the ethical considerations that shape consumers’ food choices, and to map the trajectory of a “healthy diet” from ideation to practice across various settings in Shanghai and beyond.

Building on my ongoing interest in the ethnography of restaurants, I have focused particularly on vegan and vegetarian practices in urban China since 2023. The research findings thus far highlight a shift towards more responsible consumption, with vegan eateries, organizations, and communities in Shanghai serving as key sites for this transformation. This research examines how consumers form their perspectives on food choices, the knowledge that informs these choices, and the roles played by state policies, the catering market, and restaurant entrepreneurs in framing concepts of healthy and ethical eating. To further delve into these dynamics, I organized two events on campus to amplify “Voices from the Research Field”, where my interlocutors from vegan restaurants shared their insights.

Your research site spans multiple locations—from Shanghai’s vegan restaurants to confinement centers and organic farms in places like Yunnan and Jiangxi. What led you to these places in the fieldwork and how? Have there been some of the most interesting or surprising findings so far?

The “field” has always been an intriguingly unpredictable journey for me, especially in the context of exploring food through anthropological inquiry. Conducting fieldwork is both a process of uncovering uncertainties and stumbling upon unexpected possibilities. For instance, my research at confinement centers began as part of a collaborative project on “Gender and Care Industry” with a team from the East China University of Science and Technology. Initially, my focus was on “gender and migration” in the context of caregiver training centers. However, during conversations with trainees (postpartum caregivers) about their daily lives in host homes, food repeatedly surfaced as a central topic, both in terms of nutrition for new mothers and newborns and with their daily life arrangements within the host homes. While working with two influencers (trainers) in the caregiver industry in Jiujiang, Jiangxi province, both of whom were postpartum caregivers (yuesao), one specialized in confinement meal (yuezican) training and shared her insights on the importance of food in this context. This training not only emphasized balanced nutrition but also advocated for ethical eating practices. I came to realize that food in this context functions as a powerful symbol of care, health, and ethics, aligning deeply with the broader themes of my research.

Meanwhile, my trips to Yunnan highlighted another compelling narrative. Many vegan restaurants I visited in Shanghai frequently referenced Yunnan cuisine, specifically its rich variety of vegetables and mushroom-based dishes. Yunnan, particularly areas like Dali, has gained a reputation as a hub for vegan and vegetarian practices, often promoted by young urbanites seeking to “escape” the pressures of city life as tourist migrants. These locations have become central to understanding the intersections of food, identity, and lifestyle. Ethnographic research often requires following the stories, objects, and people that emerge organically along the way. These rich and unexpected encounters, whether in confinement centers or vegan communities, have reshaped and expanded my understanding of food, care, and ethical living.

Originally, your project did not include organic farming, but you recently expanded your fieldwork to cover this area. What led to that shift, and how has it influenced the direction of your study?

In my research, the journey of food does not simply end at the restaurant table, it extends into household kitchens, markets, and now, organic farms. These spaces provide a more intimate setting where narratives of food, health, and ethics are intricately woven, and sometimes contested. The organic farm project was an unexpected yet serendipitous outcome of city exploration. One day, while strolling through the city, I came across a store advertising itself as an “organic vegan shop and vegetarian restaurant”. Intrigued, I went inside, and my collaborator Panpan and I struck up a conversation with the shopkeeper. As luck would have it, this led to an introduction to their CEO, which opened the door for us to expand our research into the world of organic farming.

What initially seemed like an extension of the vegan/vegetarian lifestyle narrative quickly revealed itself to be much broader. The ethical discourse surrounding the organic farm is deeply tied not only to food practices but also to issues of environmental concerns at local, national, and global levels. Interestingly, the farm was originally initiated with a practical goal: preserving traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. However, it also carries a spiritual dimension, rooted in practices of merit-making and moral cultivation.

This expansion of my research has allowed me to move beyond the restaurant and delve into the interconnected relationships between humans and the non-human world in the worlds of a moral economy. Viewed through this lens, organic farming becomes a rich site for exploring food ethics, environmental sustainability, and even spiritual aspirations. It continues to weave seamlessly into my broader inquiry into food and ethics while encouraging me to critically engage with questions of care, morality, and ecological connection in ways I hadn’t initially anticipated.

Your project combines both online and offline methods, including social media observation and on-the-ground ethnography. How do these different sources of information complement each other in your work?

My project’s combination of online and offline methods allows me to explore the multifaceted ways in which food practices, food-related knowledge, and ethics are shaped, negotiated, and communicated across different spaces. Social media observation gives me insight into curated narratives, trends, and discourses, particularly as they relate to how people and businesses present themselves and their food-related practices to a broader audience. For example, influencers in the caregiver industry or vegan restaurant owners often use platforms like WeChat, Douyin, or RedNotes to share individual stories, recipes, promote ethical eating, or advocate for environmental sustainability. By engaging with these online spaces, I can trace how ideas about food and care are mediated and circulated within specific communities and networks. I also joined a few communities and their offline activities and events.

On the other hand, on-the-ground ethnography allows me to step into the lived realities behind these online postings. Visiting confinement centers, vegan restaurants, and organic farms provides a way to uncover the nuances and complexities that are often invisible in digital representation. For instance, while social media posts about organic farming might highlight its environmental or ethical benefits, ethnographic encounters with farmers or shopkeepers reveal the challenges, negotiations, and spiritual narratives that also underpin these practices. Similarly, social media often emphasizes idealized images of veganism, yet in-person interactions at various occasions, such as restaurants, vegan events, and other gatherings, offer deeper insights into motivations, community dynamics, and identities tied to these practices. Some vegan practitioners might emphasize spirituality more than environmental concerns, while others may frame their motivation purely in terms of health benefits.

The interplay between online and offline methods creates a feedback loop in my research. What I observe online often informs the questions I bring into fieldwork, while ethnographic findings complicate or enrich the digital narratives I encounter. Together, these methods allow me to explore not just the “what” of food practices: what people eat, post, or advocate for, but also the “how” and “why” behind these practices. This holistic approach, rooted in anthropological inquiry, helps me better understand the dynamic and evolving relationships between food, identity, ethics, and social change, as they move fluidly across virtual and physical spaces.

Your research also looks at confinement meals—nutritionally tailored foods prepared for women after childbirth, often rooted in traditional practices like zuo yuezi in China. For those unfamiliar, could you explain what confinement meals are and what role they play in Chinese society today? What have you learned so far from observing how these meals are prepared and taught in confinement centers and training programs?

Food taboos and practices during pregnancy, postpartum recovery, and infant care are common practices shared in different cultures around the world. In many cultures, the belief is that the avoidance of certain food intake (food taboos) protects the health of the mothers and their unborn babies. Zuoyuezi, which can be roughly translated into “sitting the month”, is a traditional postpartum practice observed in many parts of Asia, particularly in China. This cultural practice emphasizes recovery for new mothers after childbirth through rest, specific food taboo, and restrictions on certain activities. It typically lasts for one month (or 30–40 days), during which the new mother focuses on regaining physical strength and ensuring proper care for her newborn. In Chinese society today, confinement meals (yuezican) still play a significant cultural and economic role. With the rise of postpartum care centers (yuezi zhongxin) and caregivers (yuesao), confinement meals have become a cornerstone of a booming care industry. An increasing number of influencers and caregiver training programs are entering this field, leveraging both online platforms like Douyin (TikTok in China) for paid classes and offline training at dedicated centers.

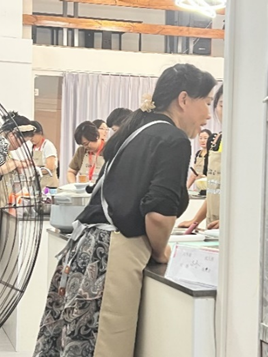

We visited postpartum caregiver training programs in three locations: Shanghai, Kunshan in Jiangsu Province, and Jiujiang in Jiangxi Province, where I observed two competing yet intertwined interpretations of what constitutes a “good and healthy” confinement meal in the training programs for caregivers (yuesao), blending principles of traditional Chinese medicine, such as recognizing different body types, with modern dietary practices. These programs underscore the importance of nutritious postpartum meals for both the newborn and the mother, which are designed to be nutritionally balanced and aesthetically appealing, fostering “joy and appetite” for new mothers to help prevent postpartum depression that aligns with the mother’s physical and emotional needs. The training of confinement meals is specifically crafted to restore physical strength, maintain a healthy weight (required by most of the new mothers), aid healing, and enhance the quality of breast milk. Commonly included are warming soups, proteins, and Chinese medicinal herbs, while “cold” or raw foods, believed to impede recovery, are typically avoided. As such, the focus on the nutritional needs of postpartum mothers tends to blend traditional ingredients like soup and red dates with contemporary understandings of health and wellness, connecting new mothers with their cultural heritage while offering tailored nutrition. The evolution of confinement meals in these settings shows how traditional practices adapt to fit modern lifestyles, balancing cultural values with practical health outcomes.

What unique perspectives does food anthropology bring to understanding urban life and modernization in China? In your view, how might your research and/or this field evolve to respond to the ongoing challenges faced by urban Chinese society?

Food anthropology offers a unique lens for understanding urban China, particularly by examining how food practices serve as a reflection of larger societal, cultural, and economic transformations. As the catering industry grows, food consumption becomes a key locus where traditional values, global influences, and individual identities intersect. From my research since 2023, I have observed how dietary preferences are shifting beyond their utilitarian origins, with vegetarianism and veganism emerging as powerful symbols of well-being, sophistication, and a modern lifestyle. These diets not only reflect changing perceptions of health and wellness but also illustrate the increasing importance of ethical and sustainable food choices in urban Chinese societies. In addressing the broader challenges of urban life, including mental health concerns, generational divides, and environmental sustainability, food anthropology continues to uncover how food is tied to ethical belief systems, community dynamics, and personal identity. My research contributes not only to the anthropology of food but also to the study of how urban Chinese society navigates these complexities through eating practices.

Looking forward, food anthropology has the potential to evolve in response to the ongoing challenges of urban Chinese society by addressing issues like food safety, the environmental impact of urbanization, and the intersection of technology with food production and consumption. For example, studies could explore how new technologies, such as plant-based meats or lab-grown foods, are reshaping urban food systems, as well as how these innovations are perceived within the cultural and ethical frameworks of Chinese society. Additionally, food anthropology can illuminate how globalization influences local food traditions and how urbanization creates new platforms for cultural exchange while raising issues about preserving authenticity. By remaining responsive to the ethical, environmental, and cultural challenges posed by rapid urbanization, food anthropology will continue to provide valuable insights into the ever-evolving relationship between food, culture, and everyday life in urban China. Through this approach, the field not only enriches scholarly understandings but also contributes to broader dialogues about sustainability and urban well-being. By ethnography of foodscapes in urban China, I hope to provide nuanced insights into the intricate nexus between food consumption patterns, ethical decision-making, and moral economy.